On The Edge.

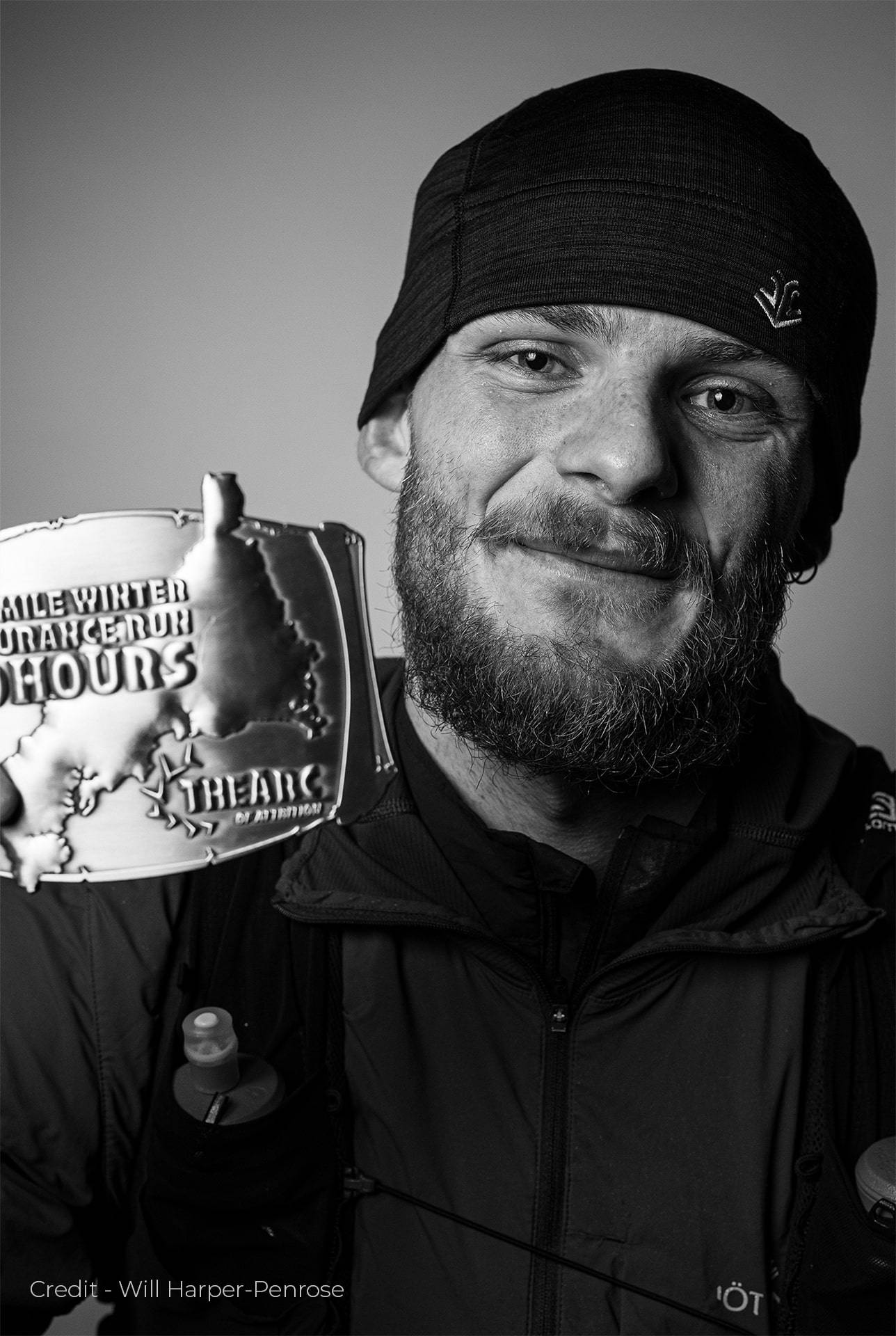

Will Brackwell recounts his joust with the Cornish coast path during the notorious Arc of Attrition.

Groundwork.

I came into my Arc training block on the back of an Ironman. Although fit and conditioned, I’d never run further than 60km in one hit. I’d have to be meticulous and dedicated. Twenty hours of training each week - more than a hundred kilometres on foot - was my prescription. Underpinning this period were the recces, fortnightly pilgrimages down to Cornwall, with weekends often spent in solitude on the coast path. During one such recce, a month out from race day, I had set off from Coverack at four in the morning, three hours before sunrise. Within ninety minutes, a storm front rolled in from the Atlantic. Winds gusting 70mph lifted me, at fourteen stone, off the ground and hurled me into hedge rows. Following a stern warning from the Coastguard, I reneged and sought refuge in a hotel on Lizard point. When a parked car flipped in the car park minutes later, I realised this was probably the right choice.

And there were other setbacks, too. A fall on my first time attempting the crux section and a fractured kneecap - which I kept to myself, not even letting my coach know. I couldn’t afford the excuse. Counterintuitively, though, these challenges increased my confidence. Knowing I had overcome difficulties in training meant I had greater confidence that I could do so in the race. In quiet moments, I rehearsed the difficulties I anticipated: poor weather, injury, nausea, sleep deprivation. Nothing novel — just a new lens to experience them through.

Onto The Trails, Into The Dark.

Race day began with quiet excitement — the weather was kind and the atmosphere brilliant - but my early impatience caused immediate trouble. Frustrated by a slow start, stuck in queues waiting to get on to the coast path, I ate too much and overreached when the opportunity presented itself to move forward in the pack. By mile 25, near Porthleven, I was already nauseous, struggling to eat or drink. As darkness fell, it got worse. Sick twice, and I grappled with the thought of another 120 kilometres of this. A friend I had made on one of my recces came past me — and I told him how I felt. “Take an hour off food and drink, let things settle,” he said, before striding off into the darkness. Sound advice as it happened: not long after I regained my composure and settled into the rhythmic flow that can come from following a head torch beam.

An important lesson learned: it will be hard, it’s supposed to be hard. But each hard moment will pass.

At mile 40, a brief, four-mile run of tarmac through the town of Porthleven was a welcome respite and an opportunity to meet my crew and friends in high spirits - but it also aggravated the injured knee, a hangover from the fracture I’d sustained in training. Over the next ten miles, approaching the halfway point, it began to seize, swollen and stiffened. Here, the body at odds with the mind: my head had settled into a rhythm and was finding enjoyment in the movement, but the wheels were starting to fall off.

The Crux.

The Arc has four possible outcomes. The most common, a fate which afflicts more than half of those who leave Coverack each year, is to DNF (did not finish). Next, finishing within the 36-hour time limit, an achievement rewarded with a “silver buckle”. A gold buckle awaits those finishing under 30 hours. And finally, for an elite few, finishing inside 24 hours earns the rare black buckle. Setting off, my fundamental goal was to finish, but I secretly wondered if a gold buckle was achievable. Due to my early mistakes, I reached halfway nearly three hours behind target pace and felt assured it wasn’t.

The turning point of my race came on that stretch between Pendeen Lighthouse and St Ives, the place the locals affectionately know as ‘Mordor’. The route description here offers little encouragement, instructing runners to follow “the most worn boulders” and to “traverse this section with other runners if at all possible for your own safety”. I knew the route intimately from six separate training runs and this familiarity allowed me to claw back precious hours. I surprised even my crew, arriving two hours ahead of schedule at the Zennor checkpoint. They had been sleeping and had to run down the trail after me, clutching my food resupply — can’t get the staff, as they say.

The Graveyard Shift.

From St Ives onward, I’d hoped for an easier finish, something like a victory lap. If I’d made it this far within the cut-offs, I figured I’d probably get to the end. Just 21 kilometres left…a half marathon. I’d already done seven of those. And this stretch was, on paper, the least technical and the most runnable section of the entire route. But somehow, that final half marathon felt insurmountable. Every step became a negotiation. I was hobbling now, running only in short bursts, walking when I couldn’t. I was hollowed out; I hadn’t eaten properly for more than a day, and the sleep deprivation was starting to play with my senses. Moving forward became a process of bargaining: just to that headland, just to that gate, just one more stretch of path.

At one point, I reached my crew station unable to speak. All I could do was peel off my vest and drop it at their feet before climbing into the van. I put my head in my hands and cried. I’m still not sure why - I didn’t think about quitting exactly; I just didn’t have the capacity to think. I was cracked open.

By the next crew point, I’d regained the ability to verbalise (just) and regained a limited sense of humour. I’d managed to remind myself what this actually was: the final few steps of a journey that had started a year earlier. I thought about the training, countless hours, thousands of miles, tens of toenails. It felt asinine to even consider stopping.

After an eternity, and far more valleys than I remembered, Porthtowan appeared. With 25 minutes to spare before the 30-hour gold buckle cut-off, I crested the final climb - the largest of the course. As I willed myself these final yards and could begin to hear the hubbub of the finish line, all those negative feelings dropped out. My family and friends clocked me… “it’s Will… are you sure… Yeah it is, it’s Will”. I couldn’t stop grinning. Escorted to a back room, instructed to sit and drink tea. Surreal. At length, confident I wouldn’t keel over, the race staff let me stand up and head outside to embrace those who had made this happen - my crew who had followed me the length of this ridiculous journey.

Why?

Reflecting on it now, the value of the Arc to me, and in doing hard things like this more broadly, isn’t in that moment you cross the finish line — however nice that is. It isn’t in the hardship of the numerous hours directly preceding it either. To me, it’s in the momentum it gives you to get out and find challenge and experience here.

Adventure has given me such a valuable perspective, shaping how I experience everything else in life, even the mundane. And I’ve been glad to find that genuine ‘adventure’ isn’t restricted to far flung mountain peaks or long trips abroad; there is plenty enough of it in nearly every corner at home, here in the UK. Sometimes, all you need is a little shove, and you find yourself right out on the edge.

Watch the short film about Will’s time on the Arc.

About Will

Will Brackwell is a former Infantry Officer, endurance athlete, and mountaineer. He’s completed first ascents in remote ranges, ultra-marathons, and long-distance triathlons. In his day-to-day, Will is a charity executive, an endurance coach, and a volunteer first responder. He has his sights set on further UK-based ultra-running challenges and records in the coming months - circle back to LEGEND magazine as these come in.